The 17th century brought a change in English standards of cleanliness. In the middle ages, public bathhouses were common and popular throughout Europe. But concern over the licentious behavior of patrons along with the spread of the plague put a damper on public bathing. People began to believe that it wasn’t safe to immerse their whole bodies in water as medical theories developed about the dangers posed by extremes of temperature and moisture. Hot water opened the skin’s pores, making the body more susceptible to “venomous air.” And cold water chilled the body and blocked perspiration. It seemed as if dirt on the skin was healthier than water.

The 17th century brought a change in English standards of cleanliness. In the middle ages, public bathhouses were common and popular throughout Europe. But concern over the licentious behavior of patrons along with the spread of the plague put a damper on public bathing. People began to believe that it wasn’t safe to immerse their whole bodies in water as medical theories developed about the dangers posed by extremes of temperature and moisture. Hot water opened the skin’s pores, making the body more susceptible to “venomous air.” And cold water chilled the body and blocked perspiration. It seemed as if dirt on the skin was healthier than water.

But Europeans were still concerned with cleanliness. They just didn’t believe that water-based methods were a safe way to achieve it. By the 1600’s, wiping away sweat and rubbing the skin had replaced bathing as the accepted way to clean parts of the body covered by clothing. Europeans reasoned that the necessary rubbing could be done by simply wearing clothes, relying on the friction of the cloth against the skin to clean it. So the custom of wearing linen next to the skin became increasingly popular. They believed it was sufficient to remove the dirt and far better than immersing the body in water.

Medical theories of the day supported this approach. Doctors believed that sweating allowed the body to expel toxins through the pores, and if they weren’t sufficiently driven out they could reenter the body and “corrupt” the blood, resulting in disease and even death. Wearing linen next to the skin protected one from disease by absorbing the toxins. Linen was the cloth of choice because it could be easily washed (unlike woolens, leather, and fur).

Medical theories of the day supported this approach. Doctors believed that sweating allowed the body to expel toxins through the pores, and if they weren’t sufficiently driven out they could reenter the body and “corrupt” the blood, resulting in disease and even death. Wearing linen next to the skin protected one from disease by absorbing the toxins. Linen was the cloth of choice because it could be easily washed (unlike woolens, leather, and fur).

A man’s undergarment was a shirt, while a woman’s was known as a shift. White linen became the standard fabric for these. But linen production was labor-intensive; flax had to be grown, rotted, beaten, combed and spun before it could be woven into cloth. As a result it was expensive, and linen cloth was often valued more highly than any other household possession.

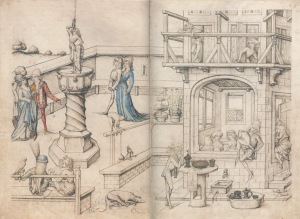

Because linens, especially undergarments, were supposedly swarming with toxins after a day’s work, they had to be washed often. From the beginning, laundry was regarded as women’s work. It was an exhausting, lengthy process, rarely done alone. The practice of weekly washing didn’t emerge until the late 1700’s; instead it was a seasonal, group task. Large amounts of water had to be heated for both washing and rinsing; the linens had to be beaten (or “bucked”) Stains were removed by soaking clothes in urine overnight. Soap-making was also a lengthy process that took a week or more, using tallow (rendered animal fat) and lye (made from ashes).

Though the English colonists valued cleanliness, the natives regarded them as dirty and smelly. Natives bathed their bodies regularly and didn’t make a connection between water and disease. The skins and furs they wore were weather-resistant. Over the generations, we seem to have combined both approaches to cleanliness – we bathe regularly, wear weather-resistant clothing, and also do loads and loads of laundry.