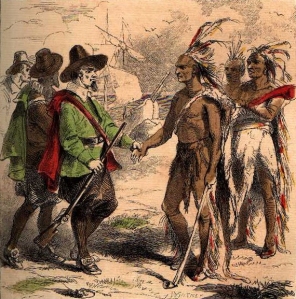

Even before the Puritans met any Native Americans face-to-face, they had made up their minds: Indians were filthy and beast-like, with an appetite for human flesh. What they saw when they did encounter natives, (while they found no evidence of cannibalism), served to shore up their wariness. Natives didn’t build and accumulate furniture; they didn’t tend animals. They didn’t have beds or linens. They displayed their bodies, favoring nudity and animal skins over proper English clothing. They referred to bodily functions matter-of-factly. They didn’t swaddle their babies and allowed their toddlers to run around naked. They had a habit of frequent bathing, exposing their nude bodies directly to the air and water—and to the view of others. And to top it off, they were a graceful, healthy, attractive people. As the Englishman John Josslyn, wrote, the women were “broad Breasted, [with] handsome straight Bodies, and slender . . . Their limbs cleanly, straight, and of a convenient stature, generally, as plump as Partridges, and. .. of a modest deportment.” This attraction made them all the more dangerous to the Puritans; Indians, they knew, were a serious threat to the morals and piety of the Puritan community.

Even before the Puritans met any Native Americans face-to-face, they had made up their minds: Indians were filthy and beast-like, with an appetite for human flesh. What they saw when they did encounter natives, (while they found no evidence of cannibalism), served to shore up their wariness. Natives didn’t build and accumulate furniture; they didn’t tend animals. They didn’t have beds or linens. They displayed their bodies, favoring nudity and animal skins over proper English clothing. They referred to bodily functions matter-of-factly. They didn’t swaddle their babies and allowed their toddlers to run around naked. They had a habit of frequent bathing, exposing their nude bodies directly to the air and water—and to the view of others. And to top it off, they were a graceful, healthy, attractive people. As the Englishman John Josslyn, wrote, the women were “broad Breasted, [with] handsome straight Bodies, and slender . . . Their limbs cleanly, straight, and of a convenient stature, generally, as plump as Partridges, and. .. of a modest deportment.” This attraction made them all the more dangerous to the Puritans; Indians, they knew, were a serious threat to the morals and piety of the Puritan community.

At the same time, the New England natives had reservations about the personal habits of the colonists. English clothing, while it was useful to wear for ceremonies or as a sign of friendship when meeting with the English, was unpleasantly confining, often uncomfortable, and even hazardous. It threatened to soften their robust bodies which had hardened through regular exposure to fresh air. It was restricting to movement when working and harbored lice and other parasites. It hindered bathing and anointing skin with moisturizing and protective agents. The English habit of wearing long linen shirts (or shifts) under their outer clothes to absorb sweat and dirt held no attraction. They did not want to follow the English practice of washing linens regularly. The prospect of regularly sweating over kettles of boiling water and scrubbing out stains with harsh soaps did nothing to increase the appeal of adopting English clothing. Natives had no desire to give up their skins for English linen shirts.

The two cultures had profoundly different approaches to personal cleanliness. Both seemed practical in the context which generated them. But when circumstances brought them into close proximity, these differences became one more opportunity for misunderstanding. It took generations for these differences to fall away and make room for a new synthesis.

Yet now we live in a time when most people accommodate to seasonal changes by exposing more or less of our bodies to the open air. We anoint our skin with moisturizers. We tend animals in our homes and accumulate furniture. We speak matter-of-factly about bodily functions. We no longer think regular baths are dangerously sensual. We regularly bathe and we also wear sweat-absorbent underclothes that require us to regularly do laundry.

The daily habits of the culture we grow up in will always seem normal to us. But we humans are wired so that, when we encounter people whose customs are different than our own, we gradually adopt the ones that enhance our lives. It’s only when we encounter people whose customs are quite different than ours that we can judge the relative worth of our own habits.